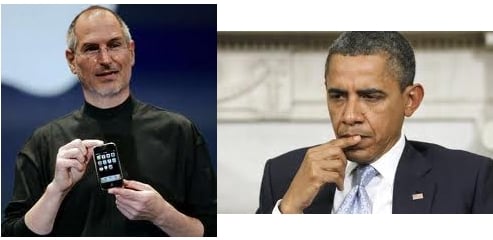

The title of this post was a question posed by President Barack Obama to Steve Jobs nearly a year ago at a dinner attended by the tech glitterati. Mr. Jobs reportedly responded succinctly: “Those jobs aren’t coming back.”

In Charles Duhigg and Keith Bradsher’s New York Times article “How the U.S. Lost Out on iPhone Work” , the content makes for an absorbing read.

Not long ago, Apple boasted that its products were made in America. Today, few are. Almost all of the 70 million iPhones, 30 million iPads and 59 million other products Apple sold last year were manufactured overseas.

Political pundits and politicians alike tend to point fingers at Washington being the crux of the problem with onerous regulatory requirements. Burdensome regulations do reduce US companies efficiency, competitiveness and profitability. Businesses need to sufficiently profitable to support research and produce innovation as R&D does not itself generate revenue. If a company is on thin profit margins and facing competition from nations not saddled with such regulations, they face a greater chance of failure in the global marketplace and tend to cut back on research in favor of actual production to support the business model.

The NYT article focused on a “glass ceiling” of a different sort. During the the final developmental phases of the first iPhone, a stumbling block was encountered: Steve Jobs wanted scratch-resistant glass screens for the iPhone. Apple needed to find a means of producing millions of scratch resistant screens that combined speed of construction with superlative quality needed to be found. The fly in the ointment was that production of such a glass screen required a finesse that was a real technical challenge. Apple had given the nod to Corning Inc. to manufacture the source glass panes that would ultimately need to be precisely cut down for use in the new iPhones, but the real problem was cost. To create a facility and stock it with competent engineers in the US would be hugely expensive from Apple’s perspective, so Apple cast its bid net far and wide and netted a bid from Foxconn in Shenzen, China.

The (Foxconn) facility has 230,000 employees, many working six days a week, often spending up to 12 hours a day at the plant. Over a quarter of Foxconn’s work force lives in company barracks and many workers earn less than $17 a day. When one Apple executive arrived during a shift change, his car was stuck in a river of employees streaming past. “The scale is unimaginable,” he said.

The crux of the article is that China and other nations can compete and currently surpass the US on several important industrial fronts:

- Supply Chain efficiency and proximity

- Quality of skilled, low-cost labor

- Quantity of skilled and semi-skilled labor

- Reduced burden of environmental and labor laws

For technology companies, the cost of labor is minimal compared with the expense of buying parts and managing supply chains that bring together components and services from hundreds of companies.

This is, like it or not, one of the areas where China shines:

“The entire supply chain is in China now,” said another former high-ranking Apple executive. “You need a thousand rubber gaskets? That’s the factory next door. You need a million screws? That factory is a block away. You need that screw made a little bit different? It will take three hours.”

While the software aspects of the iPhone (and now iPad) are created in the US, the necessity for having a large base of programmers and engineers isn’t there.

“If you scale up from selling one million phones to 30 million phones, you don’t really need more programmers,” said Jean-Louis Gassée, who oversaw product development and marketing for Apple until he left in 1990. “All these new companies — Facebook, Google, Twitter — benefit from this. They grow, but they don’t really need to hire much.”

Apple doesn’t need as many US employees in the software field for this reason. It is one thing to identically image millions of devices from one master software copy as compared to actually producing the devices themselves. Actual device production is costly to scale up and necessarily consumes more raw materials requiring more workers to handle the various physical aspects of assembly, thus the inevitable drift to cheaper overseas manufacturing.

In 1995, Apple’s Elk Grove, California manufacturing facility compared as follows to Asian counterparts:

…the cost, excluding the materials, of building a $1,500 computer in Elk Grove was $22 a machine. In Singapore, it was $6. In Taiwan, $4.85. Wages weren’t the major reason for the disparities. Rather it was costs like inventory and how long it took workers to finish a task.

Corning’s vice chairman and chief financial officer, James Flaws put the US tech manufacturing this way:

“The consumer electronics business has become an Asian business. As an American, I worry about that, but there’s nothing I can do to stop it. Asia has become what the U.S. was for the last 40 years.”

The feeling seems to be held at Apple as well.

Apple’s executives believe the vast scale of overseas factories as well as the flexibility, diligence and industrial skills of foreign workers have so outpaced their American counterparts that “Made in the U.S.A.” is no longer a viable option for most Apple products. “

Curious irony. In 1984 Apple portrayed itself as the champion of individualism, freeing the gray, regimented workers of a dystopian, authoritarian place with the new Macintosh computer, only to have their devices now manufactured by a regimented, homogenously-clad workforce living in dormitories in an authoritarian nation…

Ironic indeed.