The fine folks at Forbes raised an interesting question this week: are eBooks really books? Their take is that eBooks are more like software, due to their digital nature. And yes, they are looking specifically at the education markets. But this touches on a larger debate, one that comes up quite often. Opponents of eBooks argue that they are not really books because the book experience is not the same. Now, I rarely get to dust off my philosophy degree, but this seems like the sort of debate that lends itself quite well to a simple analysis of the identity of a book. Does moving from the physical to the digital alter the nature of the item? Is an eBook a book? Or is it something else?

First, we need to establish the nature of a book. Is it a pile of papers bound together? Does the act of publishing make it a book? Or is it a broader concept, one that can be defined by content and not physicality? Let’s start with content. Roughly speaking, a book is a narrative of fiction or non-fiction, typically with a defined theme and a beginning, middle, and conclusion. We cannot use word count as an accurate measurement since most would consider a book aimed at children to be a book, yet this would come in well below the word count of a book written for an adult audience. So loose narrative structure of the written word is probably the simplest way to define the content aspect.

The physical book is also difficult to define clearly. Do you define it as a bound grouping of papers? Again, variations mean we cannot narrow it down to the type of paper, or even the type of binding used. Is the act of printing the book enough to define it as a book? Printing translates the written word to the physical world, but a book can be handwritten as well. Further, unless you are working with a manual printing press like Gutenberg, the printed word is stored electronically before ink meets paper. Given that the mere act of printing is simply transferring the electronic file to a physical form, and since the act of printing itself has moved on quite dramatically from the early days of movable typesets, it seems unlikely that this alone defines a book.

There are those who say that any printed form, bound and held together as a continuous work, is a book, while keeping it stuck behind a screen makes it “other”. They argue that a book is defined by the sum of its parts, that everything from the printed pages to turning the pages and cover art all help define “book” quite clearly. But the book does not solely exist in print or electronic form. No one objects to prefacing “book” with “audio” to form a spoken word version of a book. Yet this is even farther from the book than the purely electronic version. Listening is a different act than reading, and audiobooks by their nature exert extra editorial control that the written word does not; the inflection and tone in a narration can alter how it can be perceived and interpreted by the reader/listener. Yet the people who object vociferously to the electronic book do not bring up the audiobook. Is this because audiobooks occupy a niche so far outside the norm of a book that they pose no threat to the paper book? Or is it that by allowing for an instance where a book can, in fact, break free from the confines of printed and bound paper, a precedent is set for the electronic version to still be a book?

In fact, there is one clear way an eBook and paper book demonstrate how much closer they are to each other than an audiobook is to either of them. A paper book can be scanned into a computer and the resulting file can be converted into a readable eBook. Likewise, an eBook can be converted to a printable format, and with enough patience, printed and bound like a book. These can be done very easily with any personal computer. The act of converting an audiobook to a printed book and vice versa is far more specialized. When an ebook can convert to a paper book, and paper books to ebooks, the insistence on a strong distinction between the two gets even more silly.

So far we have seen a few ways that the basic objections to an ebook not meeting the standards of a book are flawed. The most damning and difficult of the objections, though, is with respect to ownership. At this time, due to corporate policies and concerns about copyright, many commercially sold ebooks contain digital rights management, or DRM. Because the consumer does not control the authorization or maintenance of the DRM, there is the risk, however unlikely, that a book purchased from a bookstore may become unusable in the future. This is a limitation paper books purchased from a store do not have. In addition, and as a related concern, an electronic book can be altered easily, while mistakes or changes in paper books cannot be altered but must be reprinted.

Let’s start by unpacking the concerns about DRM and whether this makes ownership an ephemeral concept. Any ebook can be downloaded and stored in an offline fashion via a hard drive or solid state storage, thus giving the purchaser some physical control over his or her copy of the book. Further, there are many solutions, some more simple than others, that allow a user to remove the DRM from an ebook entirely. Other ebooks can be purchased without any DRM encumbering them, so the DRM is not a defining characteristic of an ebook as a whole, just something specific to certain ebooks. So ownership and control can be established in an ebook regardless of DRM. While this requires some effort on the part of the consumer, this is not so different from locking one’s door to keep thieves from removing physical books from your home. Establishing ownership requires insuring the items are in your possession and if there is concern that the digital nature of an ebook removes a layer of ownership protection there are ways to address that.

In addition, ownership is not a requirement to being considered a book. If it were, library books would need to go by a new name, as libraries own books and merely loan them to patrons. The patron must abide by the library’s rules regarding the handling and care of the book, and no one doubts the library owns the book, not the reader. So while ownership may be important to a reader, it is not a defining characteristic of a book and cannot be used to remove the “book” from “ebook”.

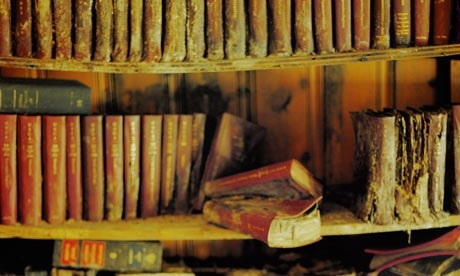

The library also gives us a way to address the most troubling objection to ebooks. A digital file is mutable, and so the written word can be adjusted or twisted even after it has been published, leading to concerns about censorship and rewrites. This is a danger with eBooks, and one that leads back to both saving offline copies as well as determining whether you have trust in the retailer selling the ebook. At the same time, school libraries have had their own clashes over censorship. A book is carried one day and banned the next, or removed and replaced with a different version. This is also an issue in countries where information is tightly controlled. So while the ebook is at risk for someone reaching in and changing it, content control and censorship is not unique to the ebook. Not to mention, a digital file is much harder to burn than a stack of paper.

In the end, it is clear that the ebook is a fraternal twin to the paper book. They share enough characteristics in common that to say an ebook is not a book is to be unnecessarily narrow-minded. Denying the ebook, while allowing all manner of children’s picture books, photo-heavy books, hardcovers with premium paper, mass-market paperbacks with poor quality paper, and other permutations of print to be “books” based solely on an arbitrary physical distinction is to ignore the true nature of a book: it is a vehicle to convey information and content using the written word. Printing is optional.