In many countries, shoppers enjoy the privilege of entering their choice of well-stocked grocery stores to find an ever-changing selection of fresh and packaged food options. Most of us probably don’t give a second thought to the people and processes responsible for producing our food; we just take the bounty for granted. But since attending the John Deere Tech Summit in Austin, I’ve gained a fresh appreciation for farmers (especially family farmers), the farming process, and for John Deere — the company that’s been helping farmers feed and clothe their families — and the world — since 1837.

Why should you care about farmers, ranchers, and their crops? Well, I’m going to assume that you like to eat and wear clothing, right? So unless you’re growing enough food and fiber on your own to feed and clothe your family, this is information that affects all of us.

To set the stage, I’m going to throw some information at you.

An Overview of Farming and Ranching in the United States

In 2021, there were 2,012,050 family and large-scale industrial farms in the U.S., utilizing 895,300 acres with an average farm or ranch size of 445 acres.

Since 1974, whether owned by a family or a nonfamily entity, a farm (or ranch) has been defined as:

Any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold or normally would have been sold, during the year. Government payments are included in sales. Ranches, institutional farms, experimental and research farms, and Indian Reservations are included as farms. Places with the entire acreage enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), Wetlands Reserve Program (WRP), and other government conservation programs are counted as farms. – USDA Farms and Land in Farms 2021 Summary, page 14

Looking at page 15 of that same report, in 1974, the minimum acreage required to be classified as a farm was removed. So, in other words, as long as the minimum of $1,000 is being made, a farm is a farm, even if the farmers are earning that gross income on one well-managed acre or less.

Over the past decade, the number of family and large-scale industrial farms and ranches, the number of acres, and the average acreage of farms and ranches have been steadily falling, and yet the USDA points out that:

Technological developments in agriculture have been influential in driving changes in the farm sector. Innovations in animal and crop genetics, chemicals, equipment, and farm organization have enabled continuing output growth without adding much to inputs. As a result, even as the amount of land and labor used in farming declined, total farm output nearly tripled between 1948 and 2019. – USDA Report: Farming and Farm Income

That’s a really amazing statement if you think about it; the USDA is crediting technological developments and other innovations for allowing U.S. farmers to do more with less; even as the amount of labor and land used to farm has declined, farming output has still nearly tripled in the past 70 years.

So, let’s talk about family farms.

Where Do Family Farms Fit In?

The USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture defines a family farm as “any farm organized as a sole proprietorship, partnership, or family corporation. Family farms exclude farms organized as nonfamily corporations or cooperatives, as well as farms with hired managers.”

Note that the definition of any farm has nothing to do with the farm’s size; rather, the USDA places farms and ranches into the following categories:

- Farms that make between $1,000 and $9,999

- Farms that make $10,000 to $99,999

- Farms that make $1000,000 to $249,999

- Farms that make $250,000 to $499,999

- Farms that make $500,000 to $999,999

- Farms that make $1,000,000 or more

According to the USDA, in 2021, 51.0% of all U.S. farms and ranches had less than $10,000 in sales, 81.5% of all farms had less than $100,000 in sales, and 7.4% of all farms had sales of $500,000 or more. [page 4 of the report]

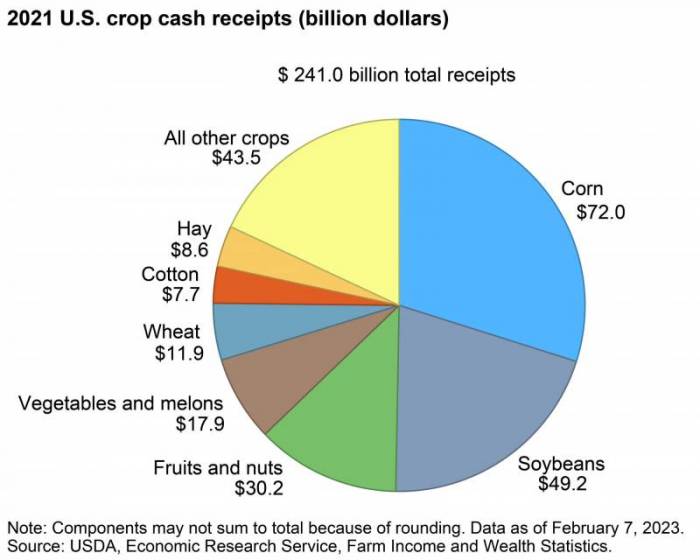

Drilling down a bit, in that same year, crop cash receipts totaled $241.0 billion, with receipts from corn and soybeans accounting for $121.2 billion (50.3%) of the total. Looking at this chart, you can get an idea of how important these two crops really are.

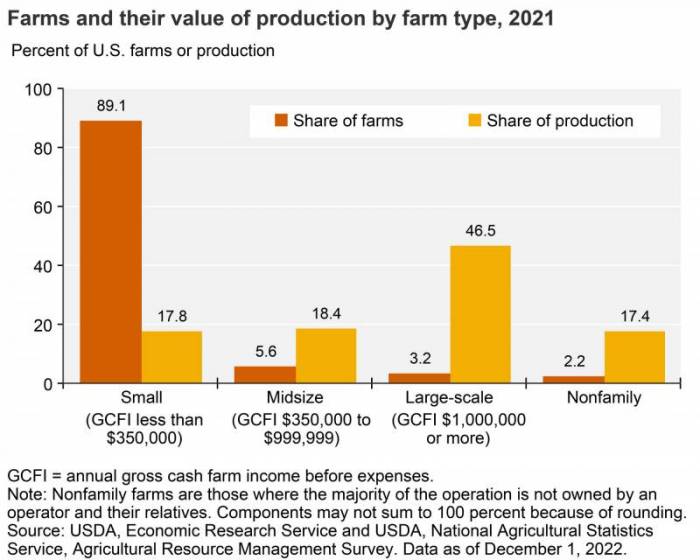

In 2021, family farms accounted for 97.9% of all U.S. farms and ranches, while nonfamily/large-scale industrial farms only made up 2.2% of all U.S. farms and ranches, although they brought in 17.4% of the gross cash farm income (GCFI).

One of the main things that differentiate a family farm from a large-scale industrial farm is how the farmers and their families are tied to the land. While all farmers must be stewards of their land, as it is their most costly and precious resource, it’s a little bit different for family farmers.

Family farmers are not in it for the quick money; rather, they are focused on sustainable farming practices that will help them earn a living wage while leaving their farms in better shape than it was when they got it so that the next generation will want to pick up the mantle and have a fighting chance at making a living versus selling out and moving on.

Back to the 2021 Survey for a moment: Small family farms and ranches, those generating less than $350,000 in GCFI, accounted for 89% of all U.S. farms, and on the other end of the spectrum, large-scale family farms, those bringing in $1 million or more in GCFI, only accounted for 3.2 of U.S. farms, yet they were responsible for 47% of the value of U.S. production.

That means that family farms ranging in size from less than one acre to as many as 190,000 acres, in total, were responsible for 82.8% of all U.S. food and fiber production.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Worth noting is that the USDA estimates that “70% of U.S. farmland will change hands in the next 20 years, but many family operations do not have a next-generation skilled in or willing to continue farming. If a farm or ranch family has not adequately planned for succession, it is likely to go out of business, be absorbed into ever-larger farming neighbors, or be converted to non-farm uses.”

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Because the “increasing popularity of local produce and direct or regional marketing is often seen as an important new opportunity for small and beginning farmers and ranchers to become financially secure. After decades of decline, the number of family farms has grown by about 4%.”

Thankfully, there are a lot of people — like this 17-year-old — who feel the pull of the land, and they are eagerly finding ways to become producers, even when they don’t have family land to inherit.

If you live in an urban area and have no experience with farming, you’d be forgiven for believing the trope that farmers are generally from an older generation that rocks a flip phone. Even as someone who lives in a rural agricultural area with 24 years of experience running a commercial cattle ranch, I had no idea how ignorant and uninformed I was.

But the fact is that a large number of the men and women running and working on family farms in the U.S. today are using the advanced and exciting technologies that have been developed by one company, John Deere.

John Deere makes tractors, combines, and other farm implements, but this is not the farm equipment of old. Today’s John Deere machinery uses A.I., machine learning, robotics, sensors, and high-resolution cameras to help modern family farmers squeeze the most productivity possible from their land. And family farms that are actively growing crops on larger plots of land are benefitting from it.

And while you might recognize John Deere’s famously green farm equipment, you might not know that in the process of helping farmers ensure that they have all of the data and equipment they need to produce their crops, John Deere has evolved to become one of the most forward-thinking, tech-focussed companies in the world.

These gorgeous antique John Deere tractors still run just fine! They might not be suitable for upgrades, though. 😉

Take a look at just a few of the farming advancements that John Deere has made:

1837 – John Deere creates a self-scouring steel plow from a broken sawblade.

1918 – John Deere introduces their first tractors, the Waterloo Boy and the John Deere Tractor

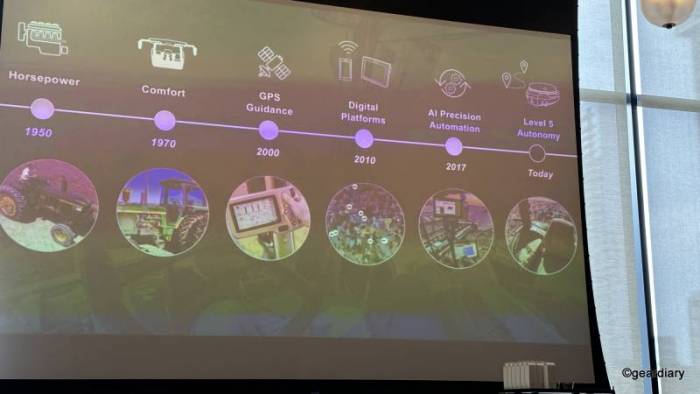

1950 – John Deere added more horsepower to their tractors so that larger-scale family farmers could work their crops more efficiently.

1970 – John Deere’s machines were more powerful, but the farmer’s comfort and quality of life during the long hours spent in their rigs came more into focus.

2000 – GPS guidance was added so that farmers could collect factual data about their farms, the terrain, and the areas that they were actively farming.

2010 – Digital platforms were added.

2017 – A.I. precision automation was added.

Today – John Deere has an autonomous tractor that can till fields completely unmanned.

The Future – Electrification. To that end, John Deere has purchased proprietary technology, which will give them an advantage. BY 2026, they have plans to deliver a fully autonomous battery-powered electric ag tractor. Crazy, right?

And that brings us to the 2023 John Deere Tech Summit

Because so few of us know what it is like to be a family farmer — or any kind of farmer, really —we were given an idea of what it’s like to be one and how John Deere fits into the equation.

Here’s a taste of what we learned and saw over the two-day John Deere Tech Summit

We were asked to consider an indoor manufacturing plant where the temperature and environment can be controlled, the people and contaminants that might enter that environment can be monitored, and every step of the process that makes the finished product can be controlled and maintained at optimal settings.

Farming is the direct opposite of that.

One of the reasons that there is so much risk in agriculture is that farming is basically a manufacturing process that takes place 100% outdoors. There are so many variables that can’t be controlled, like weather, pests, and if help will be available when it’s needed for prepping the soil, planting the seeds, caring for the growing crops, and harvesting the results, to name just a few.

Think about whatever it is that you do for a living, and imagine if you could only do the prep, get the job done, and get paid based on the results of that single project. That’s the boat that family farmers are in; they get one chance a year to plant their cash crops and bring them to harvest; if anything goes wrong, that’s it … they’ll have to try again the next year, assuming they don’t throw in the towel.

John Deere is aiming to do away with some of that uncertainty. Obviously, they can’t control the weather, but there are other ways that they can help.

Consider that there are four main components that go into farming: Tillage, Planting, Spraying, and Harvesting.

Tillage

Tillage breaks up the land and prepares it for the next job — seeding. Tillage is done in the fall after harvesting and in the spring before planting. Traditionally, it’s one of the easier, albeit monotonous, farm jobs, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be as perfectly and efficiently done as the planting and spraying.

Even so, it’s a job that traditionally requires an extra hand to handle when the farmer might need to be actively harvesting at the same time. If the family farm is on the smaller side, tillage might be handled by the farmer’s older kids, grandkids or by hired help. But that’s not always a viable solution for larger family farms’ acreage.

If the size of the farm is substantial, let’s say over 1000 acres, then that’s where the fully autonomous tractor that we first wrote about for CES 2022 will soon be able to help.

Here’s how the technology came about.

Knowing that during planting season, farmers can spend as much as 20 – 24 hours in a tractor’s cab during a plant, John Deere developed their auto-steer technology 20 years ago. Instead of manually driving a tractor for hours on end, trying to stay in a row without running over a plant or into another row, their tractors could steer themselves down perfectly aligned GPS-guided rows.

With the power of GPS and all of the automation that John Deere has brought to farmers, John Deere uses AutoTrac technology that’s smart enough that when a tractor and the implement it’s pulling come to the end of a row, the tractor will automatically slow down, turn off the putting of seeds into the ground, lift the planter from the ground, and then turn the tractor and planter without running over any of the other rows.

The tractor can then automatically align itself into a new row, put the planter back down on the ground, start dispensing seeds again, and then speed back up to 10mph … and this is all done automatically! But the catch was that someone still had to be in the tractor cab as this was going on.

John Deere took their auto-steer and auto-turning technology to a whole new level when it introduced its first fully autonomous tractor last year. Here’s what it looks like in action.

The way it generally works is that the farmer, with their John Deere dealer’s assistance, will use a StarFire-equipped off-road vehicle to get a solid GPS lock on where their fields are planted and any natural obstructions that the autonomous tractor will need to avoid.

Autonomous tractors aren’t readily available yet, but there are dozens in operation right now with harvest tillage specifically in mind. In the next few years, more farming duties will eventually be handled this way.

So imagine if extra hands aren’t readily available for any reason; tillage is yet another job that the farmer will have to do on their own, meaning extra time spent on the tractor and less time doing other things like spending time with their family. Having access to a fully autonomous tractor could easily become the farmer’s superpower, as the tractor can be controlled from anywhere using the John Deere app.

Planting

Planting is exactly what you think it is, but it’s obviously not as simple as placing a seed, covering it with dirt, hoping for rain at the right time, and waiting for the crop to grow.

Instead, planting is a 3-dimensional problem that has to consider where the seed will be placed, the temperature of the soil, and how deep the seed should be planted.

Using corn as an example for this particular scenario, we were told that farmers typically have just a 10-day window to get their entire crop planted. It can be abruptly stalled or ended if the weather isn’t cooperating. John Deere obviously isn’t able to control the weather, but it can help farmers get their crops planted as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Fun fact: next year, there will be 96 million acres of corn planted in the U.S.

When planting, fertilizer is applied to help the seeds reach their full potential, but the challenge is using just enough fertilizer so that the seeds are given their best chance without using too much, as that creates unnecessary waste, which is common with the old method of continuous fertilizer spraying during planting.

This is where things get surreal.

To help farmers become even more economically and environmentally sustainable, at CES 2023, John Deere introduced ExactShot technology, which uses 54 electrified robots to plant and fertilize each seed as it is planted.

These sensor-laden robots are able to collect a lot of data in an amazing way; for instance, there are 400 sensors on the sprayer that can keep the farmer appraised of the machine’s health and the environment that it’s in.

Using ExactShot technology, the farmer plants their crops, and their connected tractor works to clear the path, create a trench, place the seed, place the fertilizer (only on that seed), and close the trench while keeping track of everything that’s happening and where, while sharing that info with the cloud.

As each seed exits the planter, the robots will pulse, spraying only the amount of fertilizer needed (about 0.2 ML) directly onto the seed at the exact moment it goes into the ground.

Here’s a slow-mo version of how that looks.

The 24 row units on an ExactShot planter can apply fertilizer directly onto 720 seeds per second as they are planted. John Deere says that ExactShot can save over 90 million gallons of starter fertilizer per year on U.S. corn acres, which means there is much less fertilizer waste, less greenhouse gas emissions, and less risk of any fertilizer running off the field into a waterway.

Finally, closing the trench is critically important because the planter needs to cover the seed with dirt without packing it too densely. There has to be a uniform row pressure so the seed is swaddled, but not so much that the seed will have to work too hard to emerge.

Spraying

Spraying can account for up to 30% of the price for a crop, but it is a necessary step that delivers nutrients to the crop and knocks out the insects, weeds, and fungus that can appear as the plants emerge above the ground. Depending on the crop being planted, farmers might only have to spray a couple of times a year, but some crops, like cotton, can require many different types of spraying throughout the season.

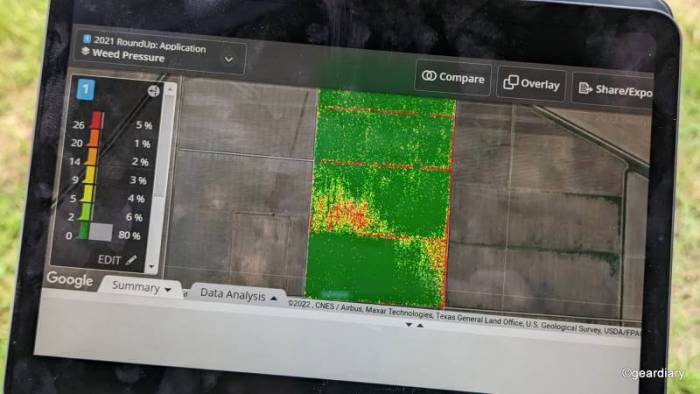

John Deere developed See & Spray Ultimate to reduce non-residual herbicide use by more than two-thirds by only spraying the weeds in corn, soybeans, and cotton crops.

See & Spray Ultimate uses a dual-tank configuration so that farmers can apply their herbicidal spray only where it’s needed while simultaneously utilizing a broadcast sprayer for fungicides or fertilizers in one pass, saving the farmer time, materials, and energy.

Thirty-six advanced cameras and 10 GPUs are placed on the spraying boom. Computer vision technology and machine learning are used to detect weeds as small as a quarter of an inch from the crops; when a weed is spotted, the sprayer nozzles are activated within 200 milliseconds, and only the weeds are sprayed.

The ExactApply system has individual nozzle controls to offer precise droplet sizing for a “consistent, targeted spray that also reduces over-application and off-target drift.” John Deere’s new 120′ carbon-fiber truss-style boom provides the stability needed to enable this targeted spray.

BoomTrac Ultimate keeps the tip of the boom within 10″ of the target boom height 95% of the time, providing a 25% better spray accuracy than the next best brand.

And finally, here’s a deep dive into what happens when See & Spray Ultimate is in use.

Think of See & Spray Ultimate as a set of bionic eyes that are continuously scanning the crops at 12 mph — in other words, superhuman abilities. S0, what is the impact of this automation on the farmer’s workload?

Thirty minutes of using automated technology in a machine gives the farmer a reduced mental workload because they no longer have to constantly scan to ensure that components are working. The generated analytics tells them where the weeds are, what was sprayed, and what is being sprayed is monitored in the machine, which builds confidence in the process.

Harvesting

When tilling, planting, and spraying have been done, the next step is harvesting, which involves cutting the crop, gathering the crop, and stripping the fruit/corn from the plant. To set the stage, when a farmer harvests their crop, they use a gigantic machine called a combine to process the crop.

When a farmer is harvesting crops like corn, soybeans, wheat, and other grains, the combine cuts the grain plant at its stalk, gathering the entire plant into the thresher, which crushes the plant, removes the grain, and sends the cleaned grain into the collection bin located on the top of the combine, so that the processed crop is propelled from the long attached auger into a tractor pulling a trailer that collects the crops.

Auto Maintain with Active Vision cameras is utilized, with one camera placed in each of the combine’s individual augers to ensure grain quality and reduce losses. AutoPath software guides the combine along the rows that were previously planted so that none of the crops are crushed or wasted.

Everything that’s not grain is expelled behind the combine back onto the field in a process that looks like this …

Now imagine that you’re the farmer driving the combine with another operator driving the tractor and trailer running so close to you. If the tractor hauling the trailer doesn’t go the correct speeds and make the proper estimation on their turns, it can be a very costly wreck.

But John Deere has a Machine Sync system where the combine and the tractor communicate with each other, and the combine essentially guides the tractor so it will be in the precise location it needs to be at not only to ensure that no harvested grain is spilled but also to make sure there are no collisions.

It’s truly mind-boggling to see the amount of automation, A.I., machine learning, and GPS technology that John Deere has added so that the farmer’s tillage, planting, spraying, and harvesting are done in the most efficient and cost-saving ways possible.

Family Farmers are Future Thinkers, Technologists, and Optimists

To prove their point about how this advanced tech works to improve the lives of family farmers, John Deere held a panel discussion with Todd Westerfeld, a fifth-generation Texas farmer who is able to manage the bulk of his 5,500-acre family farm with just three people!

Because of the time, labor, and cost savings that he is able to realize using these John Deere machines, they are able to manage his farm more efficiently, take advantage of helpful programs that require a lot of data, and still spend quality time with his family and friends; in other words, it allows him to have a life.

Todd explained how his John Deere dealer is basically a partner, long after any sales, through their continued support and help when needed.

What struck me the most about Todd was his positive outlook and how he explained that rather than any Luddite stereotypes, today’s family farmers are future thinkers, technologists, and optimists. They stay informed and engaged because they have only that one chance per year to get it right.

It’s All About the Data and Connectivity

One of the things I wondered going into this was whether all this new, beneficial tech meant farmers would have to replace their costly equipment in order to take advantage of it.

That’s not the case, however. John Deere offers over-the-air updates and modular components, including retrofitted cameras and processors for seeders and sprayers, so that these huge, incredibly pricy machines can keep going, providing farmers with the tools they need to always improve.

Data is packaged and sent to the cloud during every step of the process, where it is accessed and monitored by the farmer, whether they are the ones in the machine’s cab or not. This brings us to the next point – connectivity.

Remote display access connects farmers to John Deere dealers so they can see what is happening in the tractor’s cab and help resolve any issues along the way. Obviously, there are a lot of areas in the U.S. and Brazil that have an immediate need for connectivity because cellular data isn’t going to cut it.

John Deere’s global goal is to get up to 1.5 million machines connected by 2026 via satellite link, and they are finding ways to also make it possible for farmers in areas with no connectivity but satellite to be able to make calls as well.

To that end, John Deere collaborated with NASA to provide the necessary high-performance/low-latency infrastructure for this. They said that current connectivity use cases have the potential to unlock billions in value for the global ag industry by 2030.

So in 2004, John Deere tried something different, modifying its StarFire GPS receivers so they could tap into NASA’s global network of ground stations and incorporate JPL’s software — thanks to NavCom’s 2001 license with JPL for its GPS-correction software and a contract to receive data from JPL’s global network of reference stations.

“John Deere based their system on our technology lock, stock, and barrel,” Bar-Sever says. “We linked our systems quite tightly.” – NASA

Sustainability

But to bring it back to the family farmer, sustainability is key as the soil on their farms is their number one asset; it’s a finite resource, and healthy soil is essential for sustainability.

John Deere is helping family farmers reduce their use of synthetic fertilizers and participate in sustainable practices like planting the proper cover crops — crops that are planted after the main cash crop has been harvested to feed the soil and provide a more diverse diet for the soil’s microbes so they are healthier.

When cover crops are not properly utilized, key nutrients can be removed from the soil that feeds their primary crop, resulting in nutrition deficiencies of the main crop and a smaller harvest.

In the U.S. alone, less than 10% of the acres have cover crops on them, but there are over two dozen sustainability programs that farmers can participate in; they pay farmers to plant with sustainability practices in mind, but these programs need a lot of data, which can take days or weeks to collect.

John Deere can help with that because its machines are automatically collecting over 90% of what will be needed, which greatly reduces farmers’ headaches and paperwork.

This data collection is necessary to ensure that farmers not only can make the process more precise but also create a complete record of their sustainable practices. To that end, there is a base level of infrastructure that J.D. is seeding across their devices that offers guidance, documentation, and connectivity.

Rather than making a farmer buy a new tractor, they can install this base-level infrastructure in their current tractor, even if it’s not a Deere.

Twenty years ago, John Deere launched tractors that could drive themselves with the goal of reducing overlap by creating perfectly straight rows so they could best utilize all available acreage and ensure that end rows/headlands have the perfect precision necessary to tie into the regular rows.

Reducing overlap not only ultimately makes the farmer more money, but it also wastes fewer resources, which is ultimately more sustainable. The same thing is happening with the application of herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides.

Farmers often say that the technology they are using needs to be easy to figure out — they can’t afford to extend large amounts of time on new technology — they need to be able to use it without thinking about it. John Deere gives them a method that is intuitive and makes sense, so it isn’t a chore or a discouragement to learn and use.

Most farmers are tech savvy enough that they use a smartphone, so the touch panels in the machine’s cabs are reminiscent of a ruggedized tablet so that they have an interface that is familiar but with larger fonts, larger buttons, and increased contrast between colors so that they are easier for farmers to use.

The app is designed to show farmers that it is working and to build confidence that things are being done right when they aren’t in the machine, and only push necessary notifications when something needs your attention, as a human laborer would do.

Family farmers have so many things that have to be managed in their day-to-day work; to that end, John Deere is constantly looking for ways to help them reduce their workloads so they will stay engaged but also be able to do the other things that they want to, like enjoy time with their families and friends.

Right now, farmers around the world are responsible for feeding over 8 billion people, and that number is expected to hit 9.8 billion by 2050; if the projections are correct, it will reach a mind-boggling 11.2 billion by 2100.

Think about it; we need farmers to do even more with what they have, and it’s happening, but is it happening fast enough? Farmers, especially family farmers, have never been more important.

In 2000, farmers were able to harvest 137 bushels per acre; in 2022, that number jumped to 180 bushels per acre. It is a combination of science, genetics, and technology that has brought about this 30% improvement, and there’s no telling how much better it can be with the right practices in place.

Photo Credit: David Cogan

I’ll wrap this up by saying that, in case it’s not evident by the technology that has gone into these machines, John Deere needs even more tech-minded people with a passion for agriculture. They want to encourage people to explore the agricultural tech options that are going to be even more necessary as the tech expands.