Steve Reich – Different Trains / Electric Counterpoint

There are a few pieces of music that absolutely stop me in my tracks; that no matter my mood or intent, if these come on I will listen without fail or interruption. One is Miles Davis’ song Bitches Brew from the album of the same name … another is Steve Reich’s composition Different Trains. This music is amazing on a number of levels that I will describe later, but it also has an emotional pull, as it integrates Reich’s experience as a Jew in America with family in Europe and his thoughts about his own train rides compared to the trains carrying millions of Jews in Nazi-controlled Europe.

Let’s take a look:

Summary:

Back in 1988 I was a huge fan of both Pat Metheny and the Kronos Quartet; Metheny I had been enjoying for over a decade, whereas I had gotten into with their Monk Suite record and had recently bought an album of various works including minimalist composer Philip Glass and Jimi Hendrix. But ultimately I bought this sight-unseen based on the contribution of Pat Metheny – which is ironic since that suite is the least listened part for me. In fact, for the remainder of the review – except in the specific section for Electric Counterpoint – assume I am talking about Different Trains. It is simply that important.

Technically it is hard to wrap your head around the idea that a string quartet of minimalist music with pre-recorded analog voices, train sounds and whistles could be ‘technologically innovative’, and yet this was. It has been said that this piece has made fundamental changes to the modern views of composing and recording music, and that Reich is one of few who could be described as truly altering the course of music history.

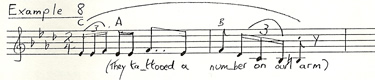

First it bears defining ‘minimalist music’. As one might expect, it is about things on a small scale – minimal. But that doesn’t make it simplistic. It is about taking a single idea and wringing everything possible from that idea. For example, in ‘It’s Gonna Rain’ Reich takes a small sample from a civil rights preacher’s speech and makes it the central theme of a tape-loop rhythmic experiment that features multiple tracks phase-offset and altered to the point that it is hard to recognize the source. His legendary ‘Music for 18 Musicians’ operates off a series of pulse trains that are harmonically simple yet rhythmically extremely complex and the intertwining of tones creates an elaborate sonic soundscape. Here is an example of writing string parts over a sampled phrase:

With that as foundation, you can see how a simple string quartet could create a work that is at once minimal and enormous – and that is exactly what happens. But it doesn’t end there. Because this is about three things: trains, the Holocaust, and Reich’s childhood travels between parents in New York and Los Angeles. Therefore there are elements of all of those included in the piece: clanging of tracks and bells, whistles of genuine trains, and the voices of his nanny and several different Holocaust survivors.

But even then there is more: rather than just using these voices as musical devices – which is how the clanging bells are used – they form the rhythmic and harmonic foundations of the various segments of the music. The train whistles are used as simple melodic shifts, and to great effect. This was a unique and unprecedented technique that was incredibly effective. But let’s dig into the music itself!

Different Trains – America-Before the War (movement 1) – The piece opens with an onslaught of the full quartet playing a rhythmic figure that is immediately reminiscent of a speeding train; the clanging bell emerging from the background adds to that effect, and it is capped by a blaring train whistle so that within thirty seconds we are ON that speeding train.

Then we are introduced to ‘text as structure’. The music changes and takes on a bouncing melodic structure over the continued driving train undercurrent and whistle sounds. We hear ‘from Chicago’ and ‘from Chicago to New York’, and realize that Reich has integrated the structure of the words into the harmonic and rhythmic structure. Then we get another change that emphasizes the minor key and slows the pace, with Reich’s nanny observing that ‘those were the fastest trains’, with an almost whimsical sound. With this fragment we also hear Reich playing with the text, taking bits of it and repeating them and creating a rhythmic contrast that adds emphasis. After more interludes recounting trains heading from New York to Los Angeles, and different New York trains, the nanny returns with another whimsical recollection of how many different trains there were before repeating the earlier structure about trains from Chicago to New York.

Then at about 6’30” into the piece we shift from the talk about trains and locations to a focus on the time in years. We start in 1939, placing us in the early years of World War II but before American involvement. The piece so far shifted tone centers between F minor and B flat minor, but now shifts to the fifth (Cm) – which is a dramatic shift and is accompanied by a change to the fastest tempo yet. Something is happening. The repetition of that year is also done differently than before, with more dense placement and more rhythmic emphasis. Next comes 1940 and 1941, with the pitch dropping and pace increasing each time and the tone of the string arrangement getting darker, with the train whistle getting louder. Then to end this movement we have the nanny observing ‘1941 I guess it must have been’ at a slower pace with the loudest train whistles yet, which leads without break into the second movement.

Different Trains – Europe-During the War (movement 2) – In one of the most dramatic, stark and emotionally impactful movement shifts I have ever heard, the transition into the second movement changes train whistles for air-raid sirens, an American voice for a European voice, a driving pulse of the strings to a slower drone suggesting a slower pace, and a more dissonant feeling to the string arrangement. The pace picks up as the story begins to unfold, and based on just the sampled fragments you get a feeling of unfolding horror. In a dramatic turn the tempo remains the same but the underlying string pulse doubles as the phrase ‘don’t breathe’ is uttered. Kids are being singled out in schools, and herded off into ‘cattle wagons’. In fact, when the phrase is spoken the train whistles return along with the sirens and the clacking of a slower train – certainly not the joyous clanking of the first movement.

The effect of the siren throughout this movement is disturbing and always has me on edge as I listen; even during the slow early sections. But when we hear about people – kids – being loaded onto cattle cars, transported for days, shaved and tattooed … it is deeply affecting. Reich’s use of repetition drives home these feelings, such as when we first hear ‘he pointed right at me’ it is repeated almost instantly as if to confirm what we had heard in disbelief.

After the culmination of the movement, things slow down and the whistle sounds stop and the music thins out to the siren, some background samples and a single violin echoing the words being spoken about flames going up into the sky and smoking. Given the context I have always associated that fragment with a solemn moment of recognition that most of the people on those ‘cattle trains’ ended up brutally killed in concentration camps. And the movement ends for us in reflection as the siren, sounds and violin fade away.

Different Trains – After the War (movement 3) – Starting with a single violin line like a single person peering out in the aftermath of a maelstrom, the third movement is both resolution and acknowledgement. The single voice is joined by others into a chorus of strings, before we finally hear ‘War is over’ in a tone more upbeat and joyous than anything since the first movement, with a repeated ‘over’ for emphasis. But nothing is ever so simple, as everything shifts to a slower tempo and somber tone as a plaintive voice asks ‘are you sure?’ against melancholy strings.

After another section provides confirmation the tempo picks up, the tune shifts into a major mode as the declaration ‘going to America’ then works us back to the trains we heard earlier as we head ‘to Los Angeles’, ‘New York’, and ‘from New York to Los Angeles’. Yet something has changed even as we hear sections repeated from the beginning – the clanging of the bells and tracks is gone, and the whistles are more subdued and the strings are less driving than before. Things have changed, and even in returning to where we were, we cannot ignore that things have changed.

The piece ends with what sounds like a recollection as part of an exchange – a girl is lamenting that ‘they’re all gone’, and remembering how the Germans cheered for one girl who sang so beautifully – without stating the obvious fact that the girl is one of those who is gone. The strings have shifted into an amazingly complex flurry effect that feels angelic to me in the background of such a sad recollection mixed with a joy of life.

The finale is quiet and beautiful and somber and reflective … I always find I need a few seconds to collect myself after the conclusion. Even now as I write this, the music has just ended and I took a few moments before continuing.

Electric Counterpoint (3 Movements: Fast/Slow/Fast) – I hadn’t yet heard ‘Music for 18 Musicians’ when I bought this record, otherwise I would have noted the essential structure shared with some of the ‘Pulses’ pieces from that work. But here we have Pat Metheny multitracking guitars and even adding bass to create dramatic effects.

There are three sections, starting with simple pulse trains, then breaking into staggered fragments before recombining. The music is ethereal at times, and pretty much rocks at others. Between the stereo spacing of the various guitars and the offset timing, each piece has a number of phases that evolve and devolve and cycle in and out. The use of heavy pulsing partial chords interspersed with lighter fragmented lines creates tremendous drama and tension. It is an excellent composition, and the selection of Metheny with solid jazz-rock sensibilities and considerable technique was inspired.

Why This Is Important: Different Trains is an incredibly impactful piece of music on just about every level. It connects emotionally based on the material and the musical structure; technically it is an incredible accomplishment that is amazing from a purely musical standpoint; it is great entertainment and an accessible introduction to minimalist music. But ultimately it matters due to the context – I won’t trivialize it by pretending it is just saying that you never know what someone else might be experiencing as they try to do the same simple daily things as you. Certainly that is part of what Reich was intending, but this is much larger – here we have someone dealing with a tragic parental split and a bi-coastal life, while having relatives dying like cattle in Europe and having the realization that were he in Europe he would be carted in a train to his own almost certain death like millions of other Jews. It is a breathtaking look at the impossible beauty of the human spirit and the cruelty of humans against one another.

Where to Buy: iTunes – $9.99 (Same price on Amazon MP3)

Here is a YouTube video with the second movement played live by the Smith Quartet as part of the film “Holocaust – A music memorial film from Auschwitz”: