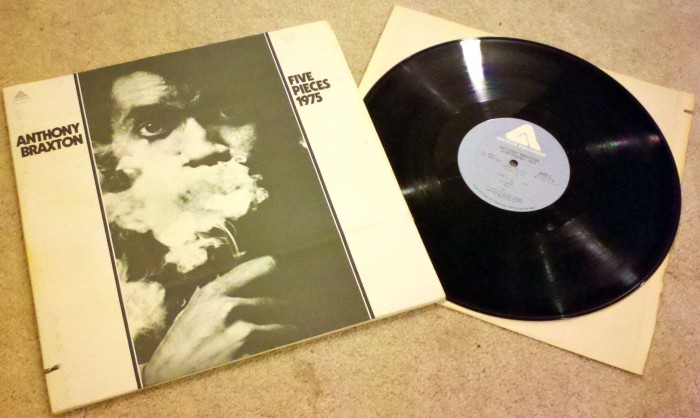

Anthony Braxton: Five Pieces 1975

One of the downsides of being a fan of music that has a very small fanbase is that very often music simply goes out of print. Like many, I have always simply assumed that as the CD came into vogue and later digital releases, music would simply be re-released. And while I can understand physical releases going out of print, it seems to be my simplistic view that once a release is digitized it should just be added to a publisher’s catalog and stay there in perpetuity.

Of course reality is never so simple, and through the years I have watched music come in and out of print. There are some that came out as a single CD run – some I caught, others I missed. Every now and then I will look back at a recording that has never formally made the transition from vinyl to the digital age.

Summary: When Wynton Marsalis and the ‘Young Lions’ arrived in the early 80’s, they heralded a new mainstream for jazz. The music ignored pretty much everything that had happened in ‘free jazz’ and ‘fusion’ from the late 1960’s to late 1970’s, instead using the Miles Davis ‘second great quintet’ as a basis. As a result, much of the great music made in the 1970’s has remained largely ignored. Pat Metheny’s early works have found popularity due to his later success, and Miles Davis 70’s work has found renewed critical success.

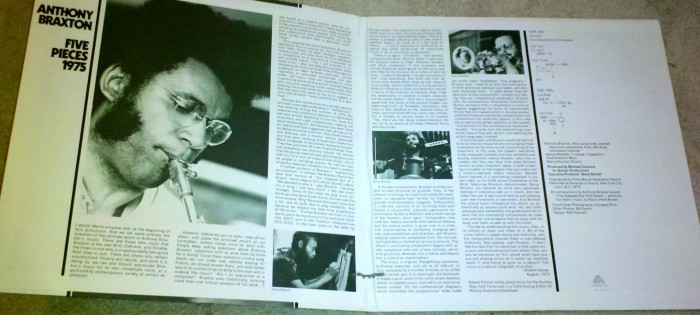

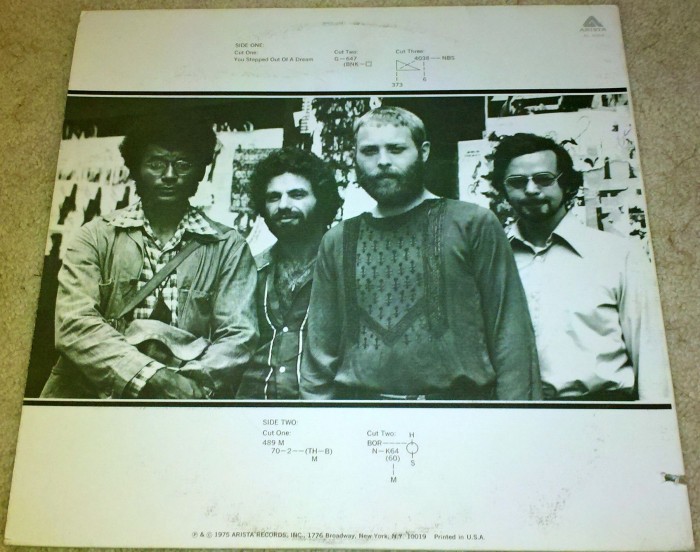

But some of the more ‘out there’ artists who recorded in the 1970s have never seen some of their greatest works languish without a re-release on CD or in digital format. One in particular is Anthony Braxton. I have always loved his ‘Five Pieces 1975’, which he recorded with Kenny Wheeler on trumpet, Dave Holland on bass and Barry Alstchul on drums.

Braxton, Alstchul and Holland were familiar with each other from past work together, including a personal favorite – Circle, which had released two live and one studio recording. Alstchul and Holland then formed

the core of Braxton’s working quartet starting in 1972, joined in 1974 by Kenny Wheeler. While Braxton (and the others) maintained active collaborations elsewhere, their tightness and communication as an ensemble continued to grow through their sessions and dates together.

Five Pieces 1975 is a snapshot not just of a band, but of an era in music. This was a time when arena rockers like The Who, Led Zepplin, Styx, Kiss and so on ruled the world … and the most popular jazz came in the form of loud fusion music from Return to Forever, Weather Report, Jeff Beck, and so on. Everyone wanted to be a rock star … or so it seemed.

Yet there was the ECM label producing the likes of Keith Jarrett’s ‘The Koln Concert’. Many artists were finding success there. Then there were folks like the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Steve Lacy, David Murray and others worked between the AACM and ECM organizations. That is where Anthony Braxton lived. While the ‘ECM sound’ was distinctly European, refined and nearly classical in many ways, the AACM was more … earthy. It was raw and direct, and while the approach was ‘free’, that often meant more that the artists could pull influences from anywhere than being a comment on the approach of the musicians.

Five Pieces 1975 consists unsurprisingly of five compositions: the first is the standard “You Stepped Out of a Dream”, and the other four are compositions by Anthony Braxton. Three are part of Composition 23 (sections H, G and E), and the album closes with Composition 40 M.

You Stepped Out of a Dream – is a standard that was featured in the 1941 film Ziegfeld Girl, sung by Tony Martin and featuring Lana Turner. You can check out that version here. The Anthony Braxton version is decidedly different – it is a duet between Braxton and Holland, with the core of the melody and harmonic structure present but dramatically altered.

Comp. 23 H – whereas the opening song is a relatively bright song, from the beginning this composition is much darker and unsettling. A very long melodic structure is played in unison by Braxton on flute and Wheeler on muted trumpet, occasionally joined by Holland on bass – though his line also takes him in different direction. Soon Alstchul moves from providing coloration to the lead role, not in a ‘drum solo’, but with a highly textured approach that never releases the tension – which is then rejoined when the remainder of the band joins back in for the improvised conclusion.

Comp. 23 G – this song sounds like it could be a straight-ahead hard-bop tune if it would ever just release the tension and drop into a standard swing structure … which it never does. The lead line is played in rhythmic unison between sax and trumpet, but the harmonies vary between the instruments. The bass and drums play a fixed staccato rhythm that is as rigid as the soloing is wild. Braxton lets loose with one of my favorite spontaneous melodic constructs – it is harsh and gorgeous all at once. These elements seem like they shouldn’t work together, yet somehow they do.

Comp. 23 E – for a song that starts slowly and with an eerie dissonant figure, Comp, 23 E slowly builds into a force of unrelenting intensity, only to have Braxton unleash some of that intensity into a wildly frenetic solo later in the piece. The song is over 17 minutes long, and has some of pretty much everything happening at some point. The bass is bowed, and Holland varies between a smooth, melodic bowing, and a manic attack that produces a guttural, frantic feeling. The drumming drives the intensity, never letting up until the very end.

Comp. 40 M – a surprisingly straight-ahead piece in approach, it features a swinging beat, an ostinado by the bass with occasional walking figures, and a strong melody interspersed with spirited improvisations by Braxton and Wheeler. It is the closest to ‘joyous’ you will find on the album, and is an amazing way to close – it is intense, bright, spirited and without pretense.

Choice Track (and why): “Comp. 23 G” – Anthony Braxton is a musical genius in many ways, from his playing to his compositions to the way he helps others find their own greatness (he has recently mentored Mary Halvorson among others). On this song he cuts through the abstract, mainstream, fusion, funk and 20th century classical in a way that represents his ideal of ‘freedom within structure’ … and it succeeds on all levels, in no small part to the amazing ensemble working with him.

You Might Love This If: You should already know and love the classic works of Anthony Braxton before seeking this one out. It is harsh, demanding and NOT an easy listen.

Where to Buy: Discogs has some used listings, but generally it is out of print.

Here is a YouTube video featuring ‘Composition 23G’:

In case you or your readers didn’t know, this album is part of the 8-CD “Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton” from Mosaic Records:

Thanks Jason – I was aware of that and had meant to add that in as a reference. Unfortunately, as noted on the page the collection (from 2008) is out of stock. It says ‘end of November’, but honestly I am not sure that even means 2011, as I have seen that there repeatedly.

Also, while all of the tracks are present, they are not presented as a cohesive whole. Opus 23 is self-contained, and You Stepped Out of a Dream is on another disc. For me that was a disappointment, as I really like the entire session together as a whole to preserve the feel.

But thanks again for pointing that out … that 8CD collection is amazing (I was fortunate enough to get it back in ’08 when it was released!)

I am not sure why FIVE PIECES (1975) has not been re-issued as a stand-alone compact disc. This is one of my ten most favorite jazz albums. Another very unfortunate omission from the compact disc catalogue, is PARAGON (1977) with Sam Rivers, Barry Altschul, and Dave Holland. When I am tired of listening endlessly to my favorite compositions by Bartok, Stravinsky, Brahms, Hindemith, Prokofiev, and such, and when I need a “pick-up,” I often turn to FIVE PIECES (1975). FIVE PIECES is not as “out there” as some of the recordings by Coltrane or by Coleman. In my opinion, FIVE PIECES (1975) is worthy of being re-issued, on its own, as a compact disce.